Adding new chickens to an existing flock can be a worrying process. Will they bring in disease? What if there is open warfare? How long will it take for them all to settle down?

Most chicken-keepers have to deal with this situation occasionally, although experience doesn’t necessarily make it any easier. That didn’t stop me from jumping at the chance of taking on four new girls in need of a home. Their owner was moving to a flat, having only bought them a few months previously, so they were still young and laying well. They were pretty hens too – Silver Laced Wyandottes and Buff Orpingtons; they seemed very docile and well-mannered. How would they get on with the wild bunch currently rampaging around the garden?

Isolating new hens before introducing them to a flock is always a good plan, even if they appear healthy and have been kept in good conditions. Stress, such as from a move, can bring out any diseases that may have been lying low. A quarantine period also provides an opportunity to worm both sets of chickens, and to give the newcomers some extra attention while they settle down in their new surroundings. All being well, they will then be fit and ready to cope with any scuffles when they take their places in the pecking order of the existing flock.

Quarantining chickens does entail having a spare coop, but this need not cost the earth and is so useful when chickens have to be segregated for any reason. Illness, injury or disputes may require removal of a bird or two at short notice, but an extra coop makes the process quick and easy. When our free-range birds faced sudden confinement during the Avian Influenza lockdown, it seemed sensible to replace the crumbling spare ark in case it became necessary to separate warring factions. For happier times, the new house and run was also suitable to use as a broody coop.

Although the run is a good size, I hadn’t envisaged it containing four plump hens. Still, it was only for a short while and they all got along very well – they even piled into the nest-box together at night. Two promptly went broody, leaving more exercise space for the others.

The girls were very happy in their new home under the trees with plenty of wood chippings to scratch in. They’d been living in a run with a base of solid earth, so lost no time in digging madly and making dust-baths. Water and food needed replenishing very frequently!

Chickens don’t appreciate having their diet changed suddenly, and it can only add to the worry of a house move, so I’d collected their remaining feed in order to make changes gradually. To help them cope with the challenges that stress can cause to immune and digestive systems, they had unpasteurised apple cider vinegar added to their water. This natural supplement can really help chickens (and indeed humans) at times of crisis. Recommended quantities (for chickens) are 20ml of vinegar per litre of water, in plastic drinkers only. My new girls arrived with their own plastic drinker – in bright pink!

After a couple of weeks it became evident that enough was enough and the new hens were becoming restless. The broodies had now gone off the idea and the run was looking very crowded. So far the existing flock had paid them little attention, but this would change when they all had to live together. It was a worrying thought. Four nicely brought-up young ladies were to be introduced to a gang of middle-aged hooligans, including three cockerels and Mr Guinea Fowl who rules with an iron beak. How would they cope?

They were transferred to the main coop at night and allowed to bed down on the floor. Previously they’d lived in a converted shed and seemed to like huddling together in a heap – probably for warmth. In time they learnt to perch, and it’s usually better for chickens to roost this way.

As expected, all was quiet until the chickens were let out the following morning. There wasn’t much trouble even then, with most of the new girls being amazed at having so much space to explore. Just one of the Wyandottes engaged in battle with the senior hen, our elderly Cochin, but they soon declared a truce and found better things to do. Giving chickens plenty of room really does help to avoid unpleasantness. The lower-ranking hens can hide if necessary and the more senior chickens tend not to worry them so much if they have other distractions.

It soon became clear that the new hens were more than capable of holding their own, and some of the older ones even seemed to be avoiding them. ‘Tweetie,’ our youngest cockerel, immediately took them under his wing, and quickly proved a most attentive suitor. To my surprise, the two older cockerels showed little interest in the new girls, clearly preferring their more mature consorts. This was probably a wise move. Tweetie soon looked exhausted trying to keep up with four feisty youngsters and could often be spotted having a quiet lie down.

The new hens have now been accepted by the rest of the flock, although each group still tends to stick together. Tweetie and his girls have to wait their turn at the feeder, with the older chickens taking precedence – after Mr Guinea Fowl has eaten his fill.

A little extra effort when the new hens arrived really helped to make the integration process quicker and less stressful for everyone. With a new pecking order established, as long as nobody gets ideas above his or her station, there is peace and harmony in the garden.

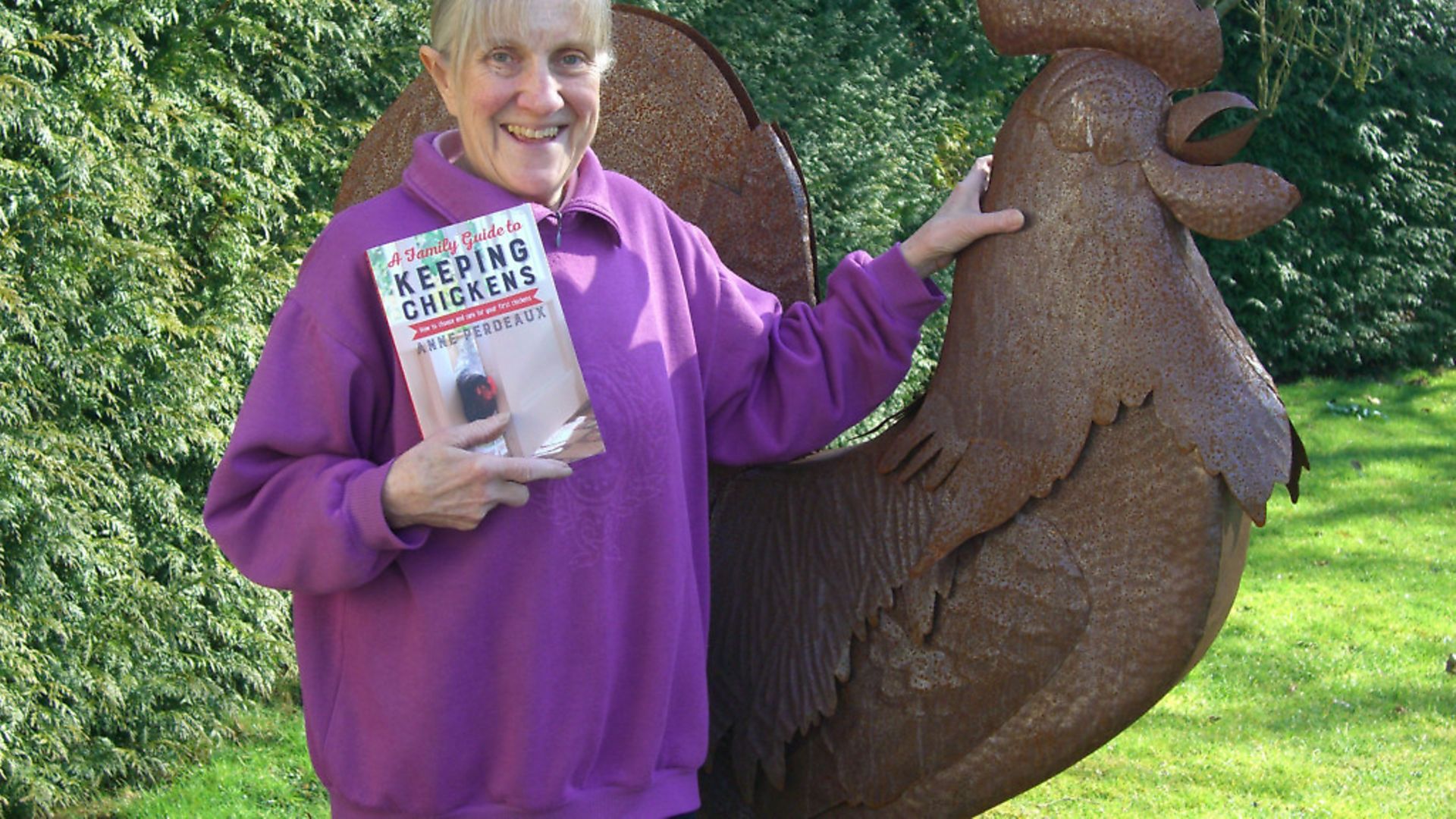

Anne Perdeaux is the author of A Family Guide to Keeping Chickens, now republished in its second edition. From complete beginner to henthusiast, there’s something for everyone, plus fun activities for the younger members of the family too.

http://bridgehouse.ddns.net/website/

Image(s) provided by:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Archant

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphoto