Countless smallholders are faced with this dilemma. Our vet, Pete Siviter, offers guidance

What a dilemma.. when should you call the vet? There are certain procedures that even a novice can tackle quite easily, and some interventions which definitely need urgent veterinary attention – and then there is quite a lot of grey area in between. We’ll be discussing how to navigate that grey area in this feature, but the real key is to know your own limits.

Other than that, it is important to remember that prevention is better than cure. Most of the phone calls I receive from smallholders concern problems that are happening now (for example: ‘my sheep are scouring’) and only a few are about how to foresee issues and prevent them (for example: ‘how should I manage or treat my sheep so that they don’t scour?’). The more we can anticipate and prevent disease, the healthier and more productive our stock

will be.

New smallholders

If you’ve recently started keeping livestock for the fist time, I would strongly advise you to make contact with your local vet and give them your details. Even if you don’t have any health issues at the moment, it will be a great comfort to know which number to dial if you need urgent help. Your new vet will also be able to give you valuable advice on worming, vaccination and preventative management to help avoid problems arising in the fist place.

A sliding scale of problems

Leaving aside prevention for the moment, let’s talk about the sliding scale of veterinary problems. At one end are problems that definitely do not require an urgent phone call, such as the elderly sow who is putting on weight or an orphan lamb who is not mingling with the rest of the flock. These situations may benefit from a conversation with your vet, but they are not emergencies.

At the other end are absolute veterinary emergencies that even the most experienced farmer could not deal with on their own. The classic example of this is the birthing ewe whose lamb is so large that a caesarean section is the only viable option – this cannot be safely or legally performed without veterinary assistance.

In between these two extremes are all the other maladies and conditions that affect our animals, and response to these will depend on your own experience. If you have successfully dealt with a particular condition before and you are confident in recognising it, choosing appropriate treatment and providing aftercare, then it is perfectly reasonable for you to ‘fly solo’ on that one. However, if you’re dealing with something new and unknown where your treatment would be based on guesswork, you must seek professional advice before proceeding.

Remember, whether or not a vet is required, it is your duty to attend to that sick animal straight away. Venienti Occurite Morbo is the motto of the university where I trained, meaning ‘Confront disease at its onset’ and I think this is a good mantra for smallholders too.

Three rules of thumb

1. An emergency is an emergency. If ananimal is dying or in distress then you must phone the vet straight away. The most common emergencies that we deal with

involve birth, bleeding and broken limbs, but there are of course many situations that require immediate veterinary attention.

2. Prevention is better than cure, andyour prevention strategies should be laid out in a Veterinary Health Plan. If you haven’t already got one, you should pay for an hour of your vet’s time to sit down and discuss your requirements so that they can produce this document for you.

It will contain everything you need about vaccinations, wormers and fly control, as well as appropriate treatment strategies for common ailments so you know what to do when problems crop up.

3. Don’t be afraid to ask silly questions.Livestock are full of surprises even for the most experienced countryman, so the more you can communicate with farmers, vets and fellow smallholders the more proficient and self-sufficient you will become.

What you CAN do

1. Monitor for disease and examine the patient

We’re required by law to visually inspect all of our animals at least once a day, but what does that really mean? Casting a quick eye over the flock or herd might make you feel better but it doesn’t constitute a proper inspection. This is where the art of stockmanship comes in – observing animals’ behaviour carefully and knowing or feeling when something isn’t quite right. Allow yourself to observe normal activities, particularly breathing (which should be relaxed and regular), eating, drinking, cudding (for ruminants), urinating and dunging.

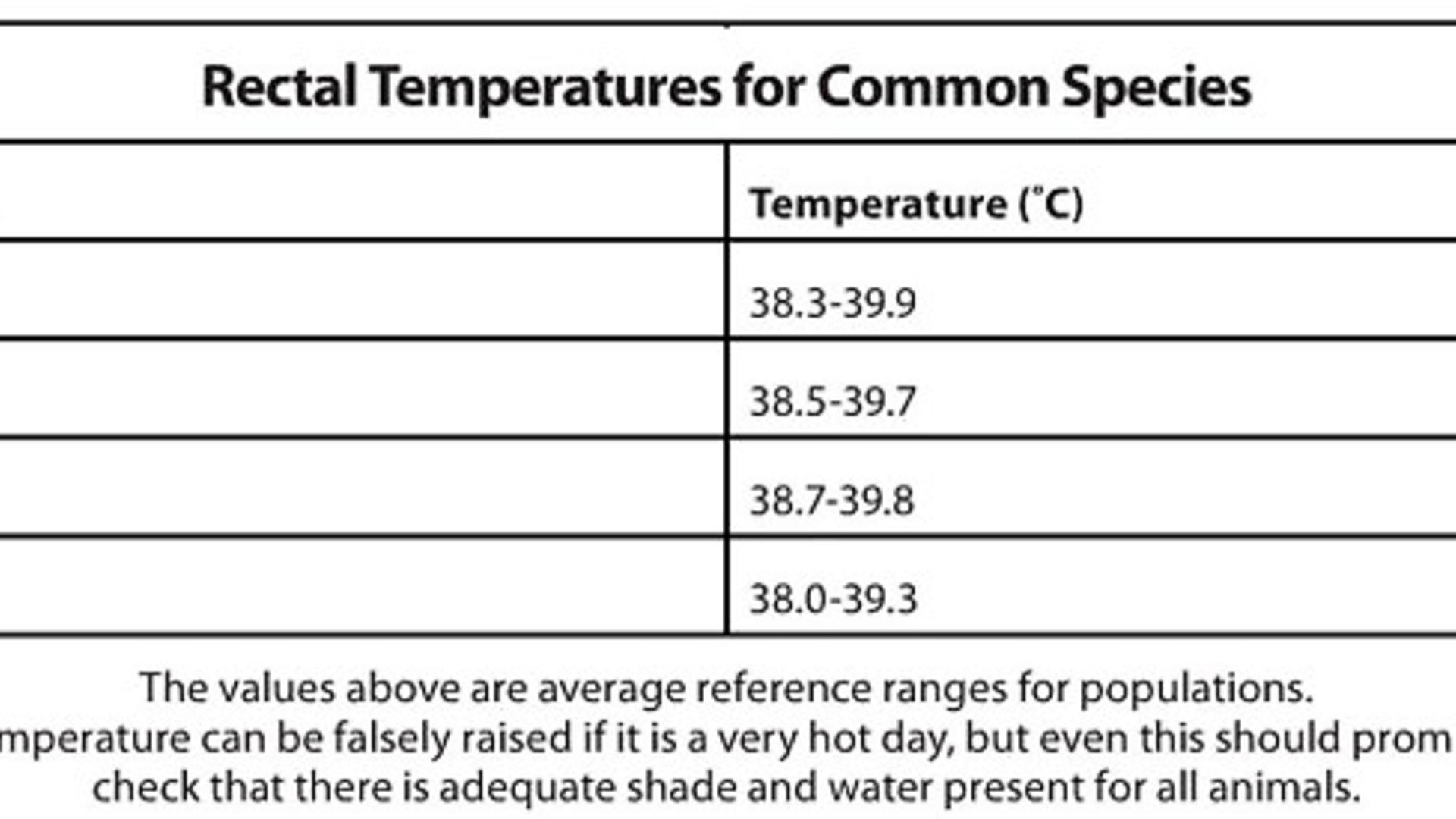

Any individual that catches your eye as being abnormal should be singled out and given a more thorough objective examination. Eyes, teeth and toes commonly cause problems so it is always advisable to check those, as well as a good assessment of the fleece, hair or feathers (depending on species!) to check for lumps and bumps, injuries and parasites. I would suggest that any stockperson would also benefit from having a rectal thermometer, which is an invaluable tool when it comes to monitoring for disease. A high temperature may indicate heat-stroke, extreme stress or infection, whereas a very low temperature may indicate hypothermia (especially in suckling animals) or shock.

2. Administer medicines

Most common species will require medications to be administered from time to time on the farm. Hopefully this will only involve routine treatments like vaccinations (which may be specifically tailored to your holding) and worm/parasite treatments (which must be discussed with your vet to ensure a minimum effective use strategy). If you have the vet out to see a sick animal, then a course of follow-up injections may be required depending on the disease. The three most common routes of administration for medications are subcutaneous injection, intramuscular injection and oral drench.

Injections

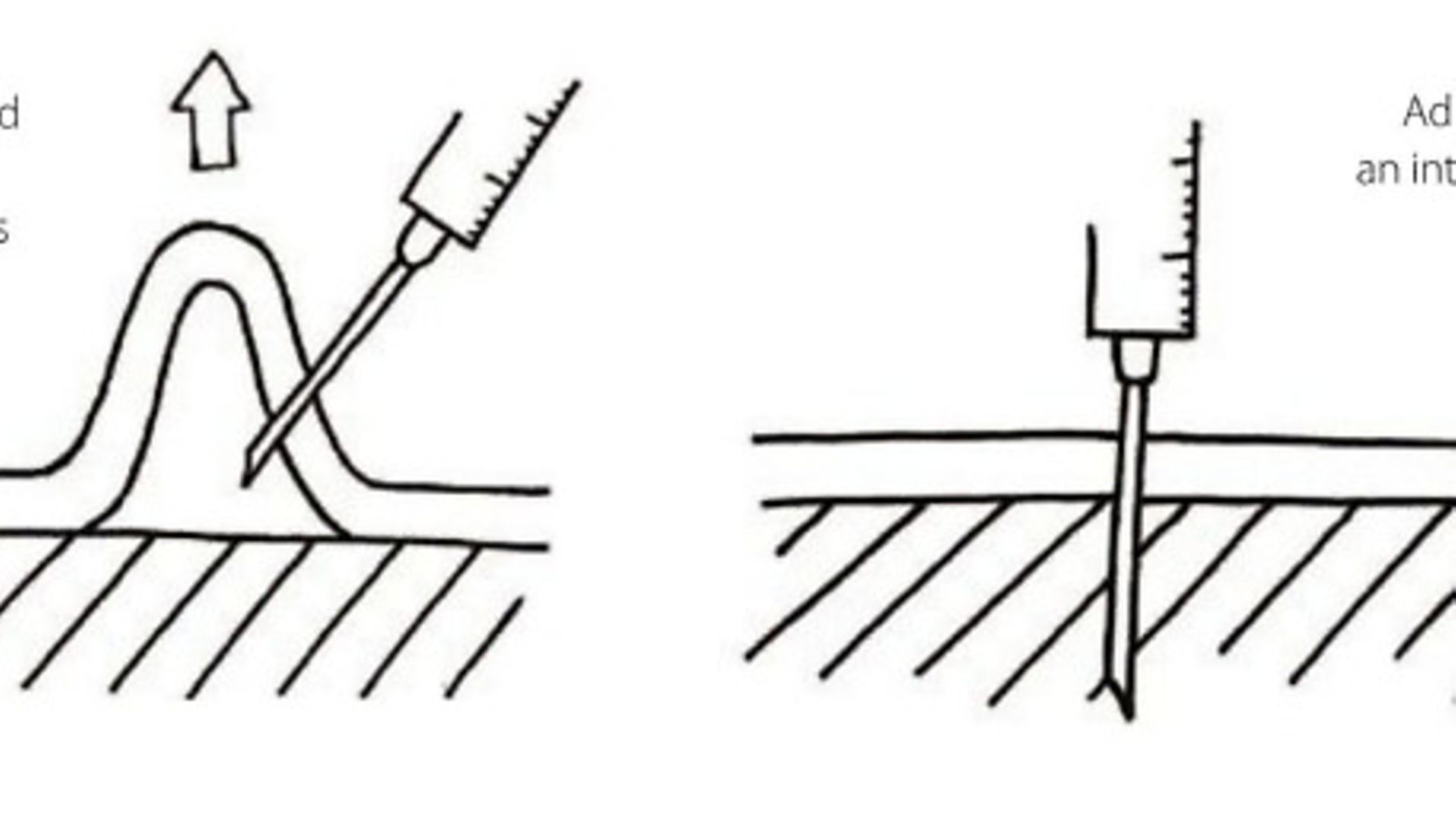

For an intramuscular (‘IM’) injection, the needle is directed perpendicular to the skin and introduced into the underlying muscle. Remember not to depress the plunger until the needle is completely in place, otherwise the contents will start to leak out beforehand and be wasted. Before injecting, always draw back briefly to ensure the needle hasn’t entered a blood vessel. The best area on the body for an IM injection is squarely in the rump on one side or another. For large fattening animals, in the neck is sometimes used because the meat there is less valuable, but this is a more advanced technique. For a subcutaneous (‘under the skin’) injection, you will need to pinch up a fold of skin with one hand to expose a small space between the skin and the underlying muscle (see diagram). Into this space the needle is introduced at a 45 degree angle and injected there. This may leave a noticeable ‘bubble’ of fluid under the skin for a few hours, which is perfectly normal. A good place to find loose skin in small ruminants is behind the elbow or just in front of the shoulder.

Injections: An important caveat

If you’ve never performed an injection before, ask your vet to demonstrate the next time you see them. Injections are simple once you’ve done a few, but needles can do some damage if used incorrectly!

Oral drench

This is a technique used mainly for worm treatments in sheep. Most oral products can be supplied with a ‘dosing gun’, which must be calibrated before use to check the volume dispensed is correct. This is easy to do with an ordinary measuring jug. The animals must be weighed before administration to ensure accurate dosage. With the sheep properly restrained, the nozzle of the dosing gun is introduced into the side of the mouth and then down over the tongue. Pull the dosing trigger fully and it’s a simple as that! A calm, quiet attitude is invaluable when performing interventions such as these, especially in prey animals like sheep.

First Aid

It goes without saying that in the case of a true emergency, anything you can do to help before the vet arrives will be of benefit. If you are familiar with first aid in humans, then the principles of ‘Airways, Breathing and Circulation’ are exactly the same in animals. Try to get the beast in a comfortable position, ensure airways are unobstructed and if something is bleeding put pressure on it!

In conclusion

There are never any hard-and-fast rules when it comes to keeping livestock. Do what you can, always put your animals first, and rest assured that we vets are available if you need us!

Worming

Worming drenches for sheep should always be targeted and based on worm egg count data from your animals. Regular (i.e. blind) worming is strongly discouraged due to the rise of multi-resistant worms, which are now very common all over the country.

Image(s) provided by:

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Archant

Archant