Vet Pete Siviter advises how to be on your guard for chronic liver fluke this winter

Sheep are susceptible to a variety of internal parasites and worms, which invariably spend a portion of their lifecycle developing on the pasture before being ingested. In the depths of winter these external larval stages generally die or hibernate in one way or another, so you could be forgiven for thinking that sheep are not likely to suffer from internal parasites at this time. In the case of gut worms it’s true, but the important exception is liver fluke. The liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica, is a more complicated organism than the usual worm species and has a multi-stage lifecycle that takes several months to complete. For this reason, there is not a single discrete risk period.

Factfile:

The parasite requires moisture and mild temperatures to complete the first part of its life-cycle, which is spent developing on the pasture and within tiny mud-snails

Clinical disease is classically seen in the autumn because this is when adult fluke reach the liver in large numbers, having spent several further weeks maturing inside the sheep

Depending on weather conditions, a second wave of developing fluke can reach the liver and cause chronic disease early in the New Year, even if treatment has been administered in the autumn.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of chronic liver fluke can be based on faecal egg counts, but it is best to anticipate problems before they become severe. Useful resources include abattoir liver reports (from cull ewes), parasite forecasts and a knowledge of your own flock history. If necessary, your vet may be able to use blood tests to build up a more complete picture.

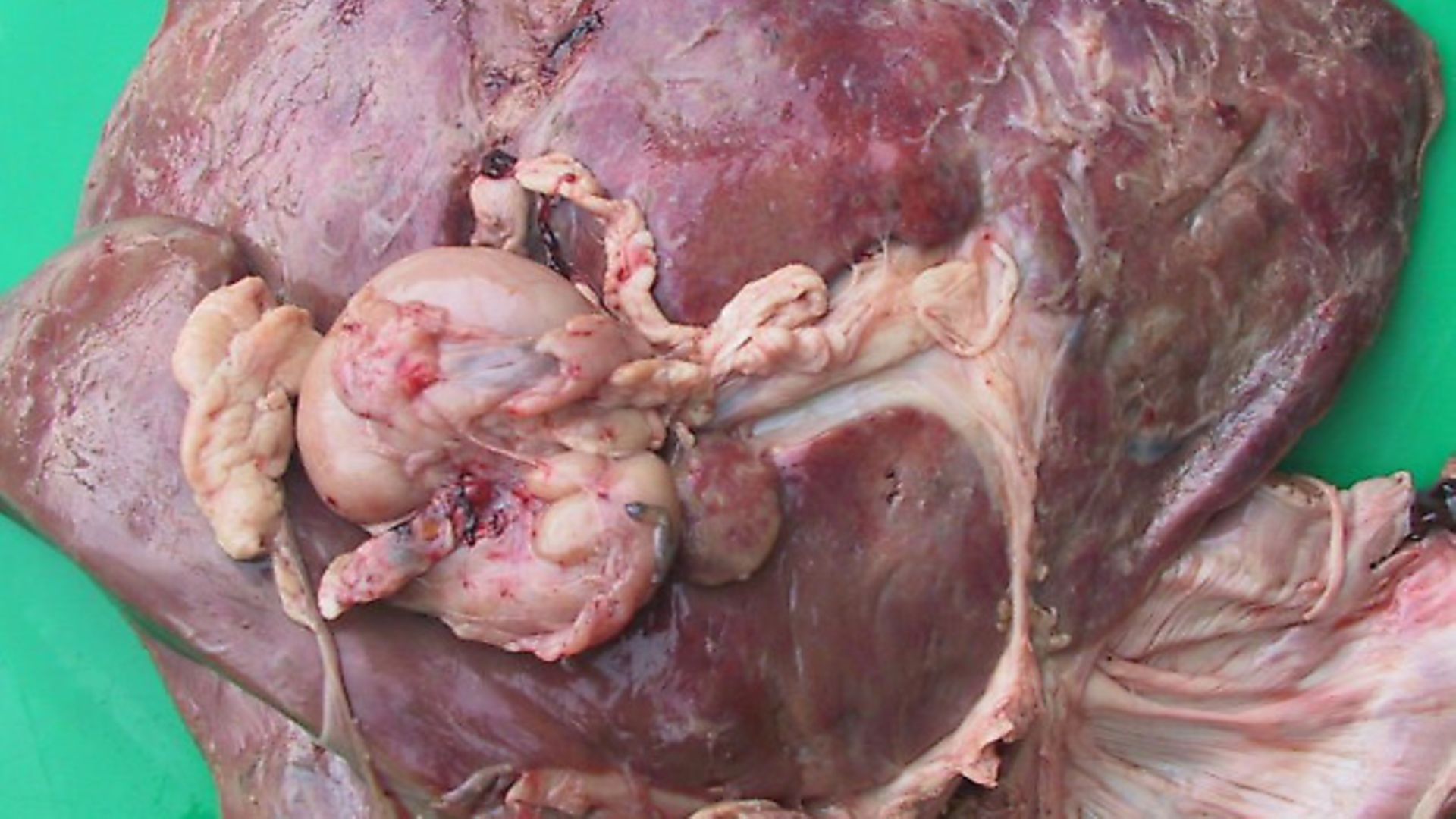

Whilst acute liver fluke in the autumn may result in dramatic findings such as bottle-jaw (see picture), anaemia and sudden death, chronic disease may not be immediately obvious to the naked eye; its effect is more insidious and leads to poor growth rates, decreased immunity (exacerbation of other diseases) and general ill-thrift.

Treatment of liver fluke is specifically related to its lifecycle. Always consult your vet, but triclabendazole should be avoided in the new year because it is the only compound available that kills every stage of the parasite and as such it should be preserved for use in acute disease during the autumn. Products which target the later stages of the lifecycle should be used in January.

FORECASTS: The National Animal Disease Information Service (NADIS) provides monthly parasite forecasts (www.nadis.org.uk), which are an invaluable tool for informing treatment decisions.

Image(s) provided by:

Archant