John Wright talks to a producer who offers free range woodland eggs in Gloucestershire

We spotted the sign for Billy’s Free Range Woodland Eggs in the Stow-on-the-Wold post office in Gloucestershire – worth investigating, with the intriguing word ‘woodland’.

‘Billy’ is really Darren Bayliss, but he prefers his high school nickname. “Everyone calls me Billy,” he tells me. Living on his parents’ Kiln Bank Farm just outside ‘Stow’, it was six years ago when he began with 90 chickens acquired from a neighbour who sold roadside eggs. At first, Billy housed them in small home-built chicken sheds which came with the birds; then, as roadside sales increased, he bought garden sheds, converting them to take 100 birds each. Reaching four sheds, he decided to pursue a commercial scale and bought a Smiths Sectional Building (his Shed B) to hold 300 birds, and now produces eggs on five of their 15 acres where 2,800 chickens happily roam free in woods near their sheds.

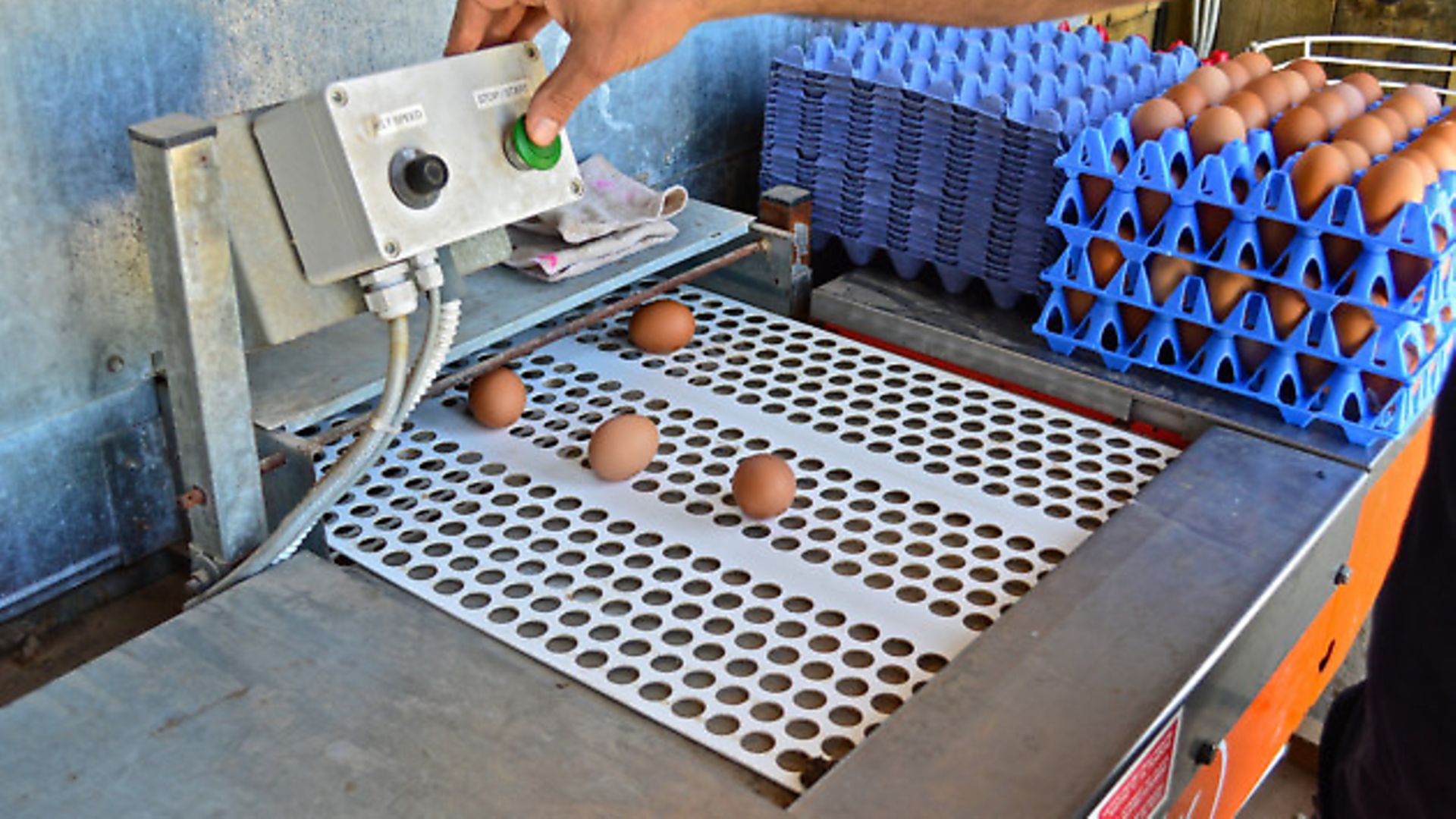

It’s a small family-run business he runs with his mother and two assistants who collect the eggs at 10am and 1pm – 2,500 a day at its peak – Billy delivering twice a week to retailers in local towns like pubs, restaurants and shops. “I’m selling about 17,500 eggs a week now, all of which are delivered well within four days (when an egg’s at its best) and we try averaging 85/90 per cent production throughout the year.”

Billy maintains a continuous supply with flocks in three sheds, producing eggs at different times. “I plan to buy more chickens (hopefully stock up to 3,500 this year) but I make sure I get the customers first so the eggs are sold before they’re laid. We often collect the eggs and deliver the same day.”

He explains his woodland idea. “Chickens are essentially a jungle fowl. They don’t like it when it’s too bright, too windy or with no overhead cover.” This is why Billy recently bought Halo bird shelters which his children say look like chuck trampolines, placed in fields with less tree cover for the birds to shelter under for security. “The protection the woodland offers can increase egg production by 9 per cent. They get to peak percentage more quickly; it’s all to do with minimising stress,” he says.

Billy remembers when his interest in chickens began. “My wife used to do baking so I bought 20 chickens to keep her supplied with eggs. They all laid an egg a day and I thought, ‘I quite like this.’ But the learning curve is vertical when you go from having a few chucks in the garden to having them commercially.” Now their children help, his nine-year-old son enjoying ‘the heavier work’. “My six-year-old daughter enjoys going into the sheds collecting floor eggs. One day, after some time, I asked if she was OK and she replied, ‘I’ve got to do a proper job, Daddy.’”

Billy says: “Chickens go back to their roots in woods, and we’ve planted 250 more trees in the last three years.” We walk up a hill to see his established coppice of hawthorns adjoining one of three sheds (Shed B, which Billy extended to hold 600 chickens and re-creosotes every year, successfully warding off red mites). Below, is Shed C, housing 1,200 birds. Shed A – an existing barn (where they feed, sleep and drink) modified with slats, feeders and nest boxes, next to a scratch area – is at the bottom of the hill and holds 1,000 birds.

Billy is the first to admit it’s a work in progress. Shed C – a new steel-framed building he’s adapted with removable slats and an automatic feed track supplying food five times a day – is proving difficult because the birds don’t leave it often enough. At present there’s no tree cover directly around it, apart from shade cast by a big ash tree in the field. Billy has planted more trees to extend his woodland which he’s fencing in half so the birds can free range in one half while the other restores itself.

Another big challenge has been losses due to foxes. His original stocking level of 90 chickens is ominous, being the same number he lost one year. “We lost six birds the other night,” he confides. “I use a .223 rifle with a lamp attached to shoot foxes. You can see their red eyes as they come across the field. It’s a job I don’t like doing but my livelihood’s at stake.”

Lights go on in the chicken sheds at 6am and are turned off at 9pm, after feeding. Billy explains that it’s generally better if a fox gets into the sheds after dark because the chickens can’t see them. “They can kill a few and bury them outside. But the worst scenario is when one enters in daylight, which they often do when they have cubs. It’s not the fox that kills them but panic which can kill 200-300 hens all at once. It’s happened here.”

He keeps records of every chicken and every egg on their 72-week (preferably 80) journey from hatch to commercial life. All birds in Shed B he sells to farmers and some from the larger sheds. His new birds that arrive are left in for three to four weeks to get used to their environment. All point-of-lay commercial breeds, they arrive at 16 weeks old and start laying at 19-20 weeks.

He has Bovans Browns, Lohmann Browns and he’s tried Hy-Lines and Shavers. Of these, Billy, who buys 600-1,000 at a time, prefers the Lohmanns: “They’re heavier and stronger. But you have to buy what’s available at times.” He buys them from Humphrey Pullets near Winchester in Hampshire. “They’re a very good supplier and they also supply great quality feed.”

Billy sees shed maintenance as vitally important. “When the 80 weeks is up the sheds are thoroughly cleaned. I take everything out except the nest boxes and wash and disinfect so the new chickens (which presently I buy three times a year) get no bugs from the previous flock.” Before long he plans to buy flocks four times a year (March, June, August and January), a June-arriving new shed ensuring a good rotation of good quality eggs all year-round.

Some are whoppers. “One pub in Stow had a tray of 30 eggs and 28 were double-yolkers.” His eggs are sorted by size from extra large to extra small and sold accordingly. He tells me the smallest ones are popular with hotels as two make an ideal breakfast.

The romance of keeping this number of birds is tempered by the demands of maintaining good health and quality control. “An egg inspector comes twice a year. As I sell to the public each egg is stamped with my UK and packing station number. I have to meet the regulations of DEFRA, Environmental Health, and do Salmonella testing every 105 days,” Billy says. “One day late and it’s a big fine.”

Billy has noticed that his birds in Shed B don’t get poorly, but the Shed C ones occasionally get stress-related illnesses, and he’s convinced woodland plays a big part in the birds’ health. “I vaccinate for I.B. (infectious bronchitis, contracted mainly from wild birds) and E. coli, the latter being very important,” Billy says. “A few years ago we had a very wet summer and chickens died from drinking muddy water. My chickens are wormed every six weeks, and they like having an acidic stomach so I give them Ultimate Acid so bacteria don’t form in their gut.”

What keeps him going is discovering it’s a genuine, if hard, living, but he sees all the eggs go and knows that people are taking home the freshest eggs they could imagine. Convinced as he is that happy chickens will always lay a good egg, it takes someone like Billy, who is bent on making them so, to make it all come to fruition.

Image(s) provided by:

Archant

Archant

Archant

Archant

Archant