Tim Tyne investigates this age old dilemma

It is understandable that anyone who keeps livestock will, at some point, experience a desire to breed from them. If you enjoy caring for your animals, consider how much more fun it must be to have lots of little baby animals too. Stop. Think. Making the transition from having a few pets to keeping a breeding flock or herd involves a big step up in the level of commitment required. Whereas the management of non-breeding animals remains fairly constant throughout the year, and is relatively undemanding, the needs of breeding stock are constantly changing depending on factors such as stage of gestation or lactation. There is also the fact that you will suddenly find yourself with different age categories and sexes of animals on the holding, each of which will have their own specific requirements. This adds a further level of complication with regard to grassland management, winter housing and feeding. And, of course, there is all the health implications associated with pregnancy and birth — something that the owner of non-breeding animals never has to worry about.

Why do it?

If you are intending to breed from your animals then it is essential that this is planned and has a definite purpose. You can’t simply allow breeding to occur indiscriminately, and neither can you retain all of the offspring, or your holding will soon become hopelessly overstocked and the health and welfare of your livestock will suffer. Unfortunately this scenario does occur all too often on smallholdings due to the mistaken belief that it is somehow kinder to keep them than kill them. It would have been kinder not to have bred from them in the first place.

The dilemmas faced by the first-time breeder are quite different from those of the established flock or herd owner, who already has a purpose and for whom management decisions may be based on previous successes (or failures), year-on-year breed improvement, the requirements of an established customer base, etc.

The beginner, on the other hand, has to justify the commencement of a breeding programme, which may be:

• To increase the size of the flock or herd: If you have started small and want to build up, you might consider increasing numbers by retaining home-bred females, which is a very rewarding way of going about it. However, believe it or not, rearing your own breeding stock may work out to be more expensive than buying in what you require. Also bear in mind that approximately half of the animals born will be male, so are surplus to your requirements (unless your eventual aim is to return to a non-breeding management system, albeit on a larger scale, in which case you may wish to retain castrates). A proportion of the females won’t be of sufficient quality to be worth keeping either. And, when you’ve reached your target flock or herd size you will, if you intend to continue breeding, need to start culling some of the older animals to make way for the new intake.

• To preserve a rare breed: While this is indeed a worthy objective, it is not, in my opinion, the most appropriate starting point for a raw novice. The paucity of bloodlines found within a depleted population require a certain knowledge of genetics in order for a breeding programme to make a positive contribution to the overall sustainability of the breed. Also, it is vital that high standards are maintained, which means that the initial breeding stock must be of top quality. The beginner may not have sufficient experience in general stockmanship to enable him to identify suitable animals in the first place. Furthermore, any animals that are bred that do not conform with the expected standards of the breed should, on no account, be retained or sold for breeding, otherwise the actions of the breeder are actually detrimental to the breed he professes to support. Unfortunately, when these sub-standard animals are sold for slaughter they will realise only very low prices, as they are not suited to the market requirements of today (which is probably why the breed is rare). Having said that, there are definite niche marketing opportunities for rare-bred meat with provenance which are well worth exploring.

On balance, I feel that it is best for beginners to start with ordinary commercial or crossbred stock and then move over to pedigree breeding once they have gained sufficient experience.

• To produce breeding stock for sale: Whether pedigree or not, there is always a market for good quality breeding stock. However, it might take you years to make a name for yourself at that game, during which time you may have to content yourself with selling off your annual output at little more than the cost of production. Once you have gained a reputation the difficulty is holding on to it, so at no time must you let your standards slip. This means ruthless culling of anything that fails to make the grade. Have you got the heart for it?

• To be more self-sufficient: Here I am primarily referring to the production of meat and milk for domestic use, although you might also include other livestock related outputs, such as fibre and leather, together with eggs and honey. To produce your own meat it is not necessary to keep breeding stock, as you could more simply buy in weaner pigs or lambs for fattening. However, it is far more satisfying to consume an animal that you have bred yourself.

So, the definitive question is, having been responsible for that animal’s welfare from the point of conception, witnessed its entry into the world – and perhaps even assisted at the birth – and cared for it from day one, are you then prepared to have it slaughtered and take the ultimate step of serving it up at the family dinner table?

Personally, I cannot understand why some smallholders find this difficult, but I am aware that there are people who struggle with the concept. If you are one of these people, then possibly breeding livestock is not the way forward for you.

Milk production does, of course, require that the cow, goat or ewe be bred from on an annual basis and in this situation the offspring of the milking animal may be considered a by-product of the primary purpose. You must have given due consideration to the eventual fate of the calf, kid or lamb and be confident that you are comfortable with your decision, before committing yourself to milk production. In some cases, the youngsters will be reared on to follow their mothers into the herd or flock, but others may be destined for the market or the abattoir. Sadly, male dairy goat kids are often euthanised at birth as they have no value, which I think is a shocking waste. If you can’t make use of them yourself then you should pass them on to someone who’ll rear them well, give them a good life, and, when the time comes, make optimum use of the carcasses.

• To produce meat for sale: The production of meat for sale doesn’t require breeding animals to be kept for, as I mentioned earlier, you could just as easily buy in youngstock for rearing and fattening. However, if your marketing strategy involves direct sales to a discerning customer base then the additional kudos attained by the fact that an animal was wholly bred and reared on your holding is well worth having. A couple of words of warning though: make sure of your customers well in advance, ideally before the animals are bred from, and don’t produce more than you can reasonably expect to sell. This is particularly pertinent to rare breeds, where there may be no alternative outlet for your surplus. If you keep animals of a commercial type then it is not actually necessary for you to attend to the business of marketing the end product yourself, as you could just as easily sell them through a primestock auction or directly to an abattoir. Alternatively, you could sell them at a younger age, as ‘stores’, for someone else to fatten up.

• To produce milk for sale: Milk production – whether for sale or home consumption – does add another layer to the level of commitment required, over and above the basic breeding management. Think about this first, as it is something that part-time smallholders may find they simply can’t cope with. It is also very difficult to find someone else to do the milking for you if you are ill or have to be away from home. For small-scale commercial production you will also need to make a considerable investment in equipment and facilities in order to be able to comply with the regulatory burden.

As I mentioned earlier, in order to produce milk an animal needs to be bred from (although ‘maiden milkers’ do occasionally occur, particularly in goats – my parents had one that milked for years without ever having given birth), but you could make a start by buying in animals that are already in milk. This would give you the whole of one lactation to get accustomed to the routine management before having to deal with the next parturition.

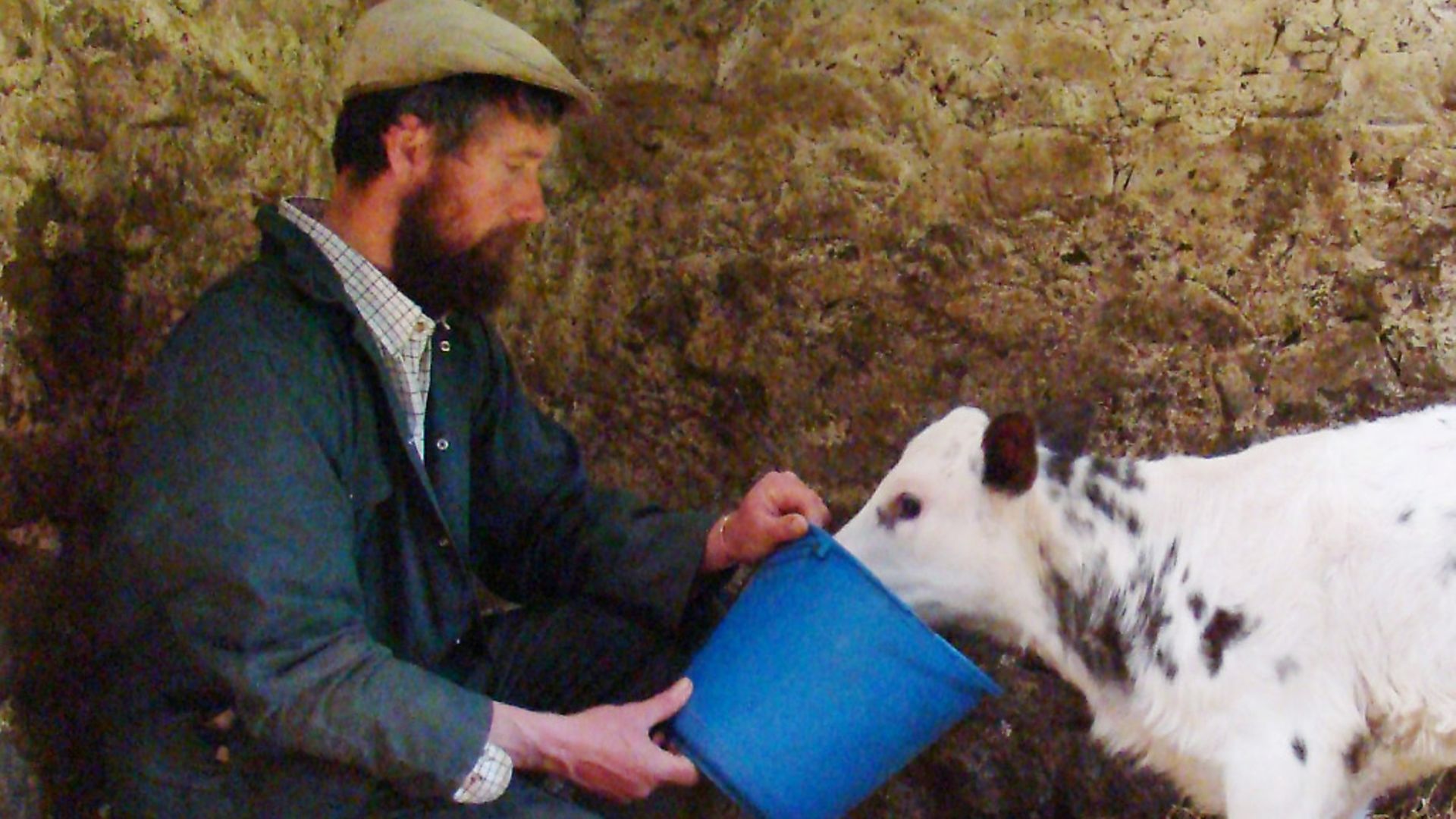

In order for milk production to be successful you will need to separate the animal from its baby at around five days after birth, or at least significantly reduce the time they spend together. You may not feel comfortable about doing this (although you may be reassured to know that none of our cows has ever complained about it). You are then faced with the challenge of artificially rearing the youngster from a very early age, which can be tricky and is a considerable responsibility. An alternative is to sell it on for someone else to rear, but again this is something you might feel uncomfortable about due to the stress involved in transporting young animals newly separated from their dams. It is essential that you have thought through all of these issues before committing to a breeding schedule.

Two additional aspects that I have not discussed are fibre production and conservation grazing, as neither of these actually require a breeding flock or herd to be kept. Having said that, conservation grazing does tie in nicely with rare breed preservation and fibre production could involve selective breeding for improved fleece quality.

Tip

It always annoys me when I hear people say that you shouldn’t give a name to an animal that you intend to eat. What nonsense. If it is your usual habit to name your animals then go ahead and give them names. It won’t affect the flavour in the slightest. We have even, at times, labelled our freezer bags with the names of the animals whose body parts they contain. Guests may find the conversation around the dinner table a little disconcerting, though, when they find that the main course is still referred to as ‘George’ or ‘Henry’.

Image(s) provided by:

Archant

Archant

Archant