In this focus on fertility, Liz Shankland looks at what you can do to maximise the number of piglets produced in each farrowing

If you are just starting out on your pig breeding venture, it might come as something of a relief when your gilt or sow pops out a relatively small number of piglets. Fewer hungry offspring mean that there should be no worries about whether or not there are enough teats to go round, so each new arrival should feed and grow well – so at least that’s one big concern off the list. And, if the pig is – like you – a first-timer, you may be pleased that she doesn’t have a massive brood to care for as she gets to grips with motherhood.

However, as you get more experienced, your attitude will change; each time she farrows, you will be willing her to produce a bigger litter to help pay for her annual upkeep and maybe even turn you a profit. Most of us develop a real attachment to our breeding sows, but that bond becomes even stronger when they become a really productive part of your smallholding enterprise.

It is thrilling when you see an in-pig gilt or sow starting to ‘bloom’ – putting on weight, getting a definite bulge in the belly and, finally, as farrowing day draws closer, her udder starts to bag up with milk. But the excitement and anticipation can turn to disappointment when she gives birth to just a handful of piglets.

Talk to experienced breeders and they have all been there. Many years ago, I had one sow which regularly had 12 to 15 piglets, but then took me completely by surprise by having a measly three. I was so convinced that there were more inside her that I carried out an internal examination and eventually called out the vet, assuming that there must be something wrong. He couldn’t feel any other piglets either and blood tests subsequently revealed no sign

of disease (thankfully). The vet put it down to being one of those things and, at the time, I didn’t question his verdict.

Litter size can’t be pinned down to one thing. A healthy pregnancy, resulting in plenty of piglets, can depend on a vast range of factors, including genetics, nutrition, timing of mating and conditions, stress and disease, and there are several ways in which you can improve the odds of a better outcome.

Grasping the breeding cycle

It is well worth getting a better grasp of how the reproductive cycle works, rather than putting your boar and sow together and hoping for the best. Here are some of the key facts you should know:

• Sexual maturity in a gilt can be anything between 150-180 days (five to six months) after birth. However, just because she has reached puberty and is able to breed, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you should breed from her. It is recommended that you wait until the third oestrus cycle (season/heat) before breeding when she is at least 210 days (seven months) old. This third heat will be much stronger than the earlier ones, offering a better chance of a good mating. Commercial breeders say she should have her first litter by her first birthday, but our traditional breeds often benefit from being allowed to grow on a little first, before being served at 10 to 12 months. Conversely, don’t leave it too late to mate a gilt for the first time; be wary about leaving it later than 12 months as older gilts can develop problems, such as cystic ovaries, that inhibit pregnancy.

• Obesity can cause conception problems, while too much fat around the cervix also makes farrowing more difficult.

• Sows are at their most fertile five days after a litter has been weaned.

• Oestrus (season/heat) occurs every 18-22 days. Gilts will remain in season from six to 36 hours; sows up to 72 hours.

• You can normally assume that a pregnancy has been achieved if there is no return to season 18 to 22 days after mating.

• If she comes back into season 23 days or more after being served, she may have been pregnant. Think back – were there any unusual occurrences which could have caused this to happen? If you have similar results in a few sows or gilts, consider having your vet take some samples for lab tests to rule out reproductive diseases.

Keep good records

Each sow should have her own health and farrowing record chart. Whether you keep this in a notebook or on a computer spreadsheet is up to you, but make sure that you also keep a pocket book or mobile phone on you whenever you go into your farrowing area, so that you can make notes of various aspects of the birth, such as duration, time between each piglet being born, farrowing problems requiring assistance, stillbirths and abnormalities. You should also note down anything unusual about the behaviour of the sow, such as aggression towards newborns or stock persons, whether she crushes or injures any, plus the number and sex of piglets born. Weeding out the poor or problematic breeders and only keeping the best could help you in the future.

Managing a good mating

Prior to mating, both pigs should be in good shape, neither fat nor underweight. If your sow has only just weaned a litter, check her condition and postpone service if she is too thin.

In an ideal world always use a boar that has an active working life because you don’t want stale sperm. Having said that, for the best quality sperm, don’t over-work him either. One service per day four to six per week) is recommended, so best practice is to keep him separate from a sow or gilt until you want her served. Another benefit is that her ‘standing’ response will be better than if she is constantly with the boar, allowing a more efficient mating.

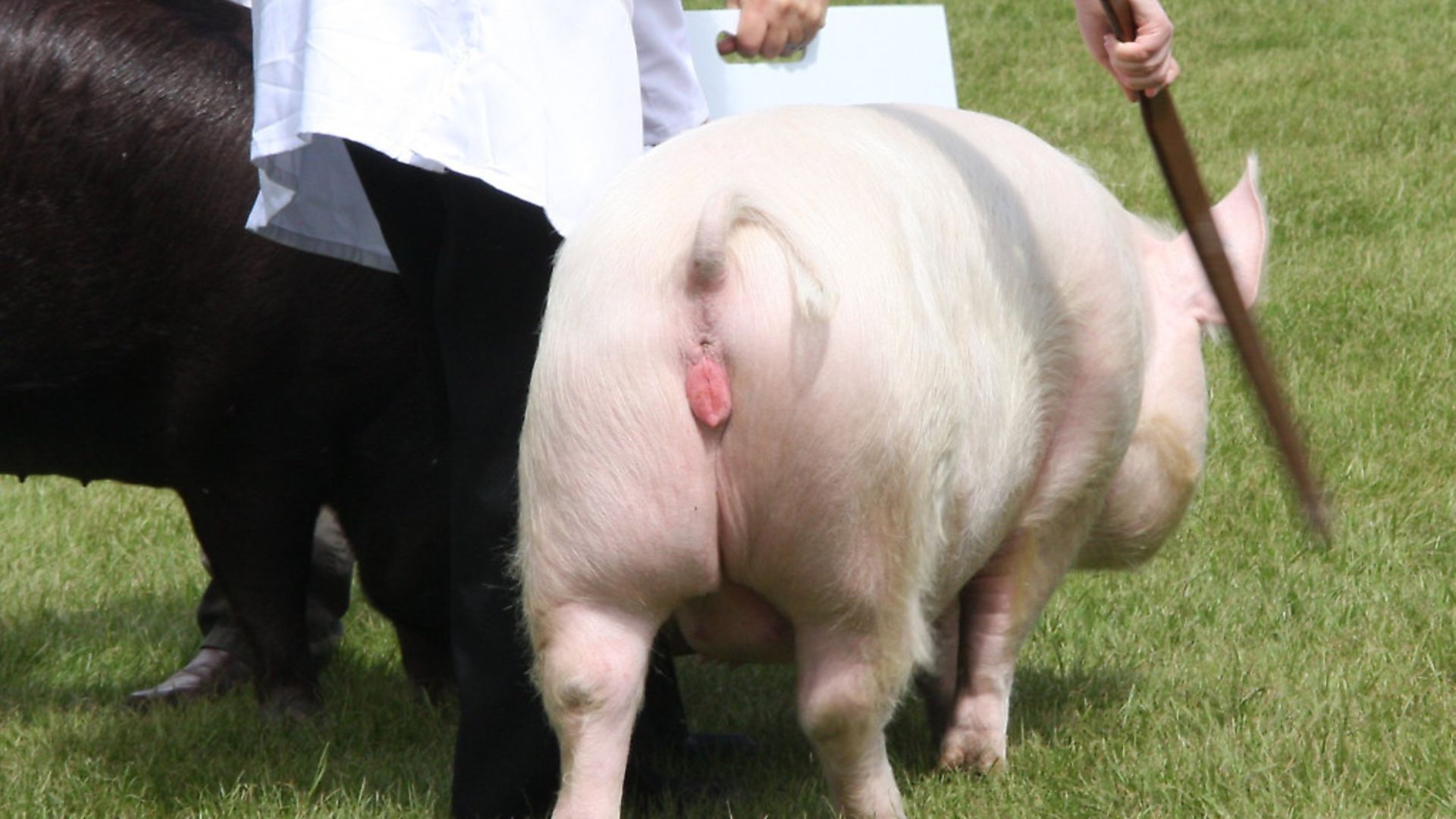

Timing of service is also important. The signs that she is almost ready for mating include a swollen, pink vulva, behavioural changes and vocalisation, but she won’t actually stand for the boar until she is in full oestrus – normally a day or two afterwards, when the swelling starts to subside – so there is no point putting her with the boar until she is ready.

Ovulation occurs two-thirds of the way through this ‘standing oestrus’ and the best time to serve is 24 hours before ovulation. Keep testing the standing reflex – by pressing on her back. As an example of when to serve, if she stands for the first time in the morning, mate her (or administer artificial insemination) in the afternoon, and repeat 12 to 16 hours later.

It is important to find a safe place for mating, which means somewhere with good, non-slip conditions underfoot and preferably away from distractions, such as other pigs. Young, inexperienced boars may need some assistance the first time because if they can’t manage to serve they can sometimes be put off for good.

After-service care

What should you do after service? Actually, nothing. That is, nothing that makes a significant or detrimental change to the sow or gilt’s everyday living conditions. Appropriate aftercare is vital for fertilisation of the eggs and implantation of the embryos to succeed. It is important to keep the sow or gilt relaxed and free from stress and to ensure that she has a good-quality, nutritious diet. Research has shown that daylight (12-16 hours a day) is essential in helping to maintain a good pregnancy, so if your pigs are being housed indoors, think of ways of getting more light into the building, such as painting the roof and walls white to increase reflection.

Image(s) provided by:

Archant

Archant

Archant