Flies are not merely an annoyance to cattle, they can transfer disease. Vet Kaz Strycharczyk explains how to limit their effects, both chemically and by using holistic methods

Flying insects of many kinds affect cattle. They can cause nuisance to animals of all ages, impacting both on their production and welfare. They can also transfer disease between animals with serious consequences. Thankfully, there are several measures that cattle keepers can take to prevent flies becoming an issue.

Fly biology

At least 20 species of fly affect cattle in the UK. They are attracted to various secretions, including tear fluid, milk, blood and urine. Some bite cattle directly, while others simply scavenge at the edge of wounds. High numbers trigger avoidance behaviour which impairs welfare and disrupts grazing. Trials in the USA suggest fly control improved calf weights at weaning by 5-10kg. This behaviour may manifest as seeking shade, restlessness, skin rippling or simply stamping and tail swishing. In extreme cases cattle may self-traumatise. Different individuals vary significantly in their attractiveness to flies and also their tolerance to fly infection. Although less common than in sheep, cattle can develop flystrike where there is a predisposing wound, often with disastrous consequences.

Flies also spread several common diseases. Infectious keratoconjunctivitis, or New Forest Eye, is a bacterial infection which flies carry between animals. The condition presents with a painful cloudiness requiring antibiotic treatment. In severe cases cattle go blind and can lose the affected eye. Summer mastitis (or dry cow mastitis) is another fly-borne infection that causes serious issues, frequently resulting in the partial loss of a functional udder.

Assessing risk

Certain holdings are more prone to flies than others. Several environmental factors feed into this, including proximity to standing water. Hedges and trees also harbour flying insects, so small paddocks with plenty of shelter can end up being higher risk than large open fields.

Risk also changes with the climate, generally increasing with warmer and wetter weather. Therefore areas in the south of Britain typically have a longer fly season than in the north. You should avoid any procedure that leaves a bloody wound, such as castration or dehorning, during fly heavy months to help prevent flystrike.

Topical medications

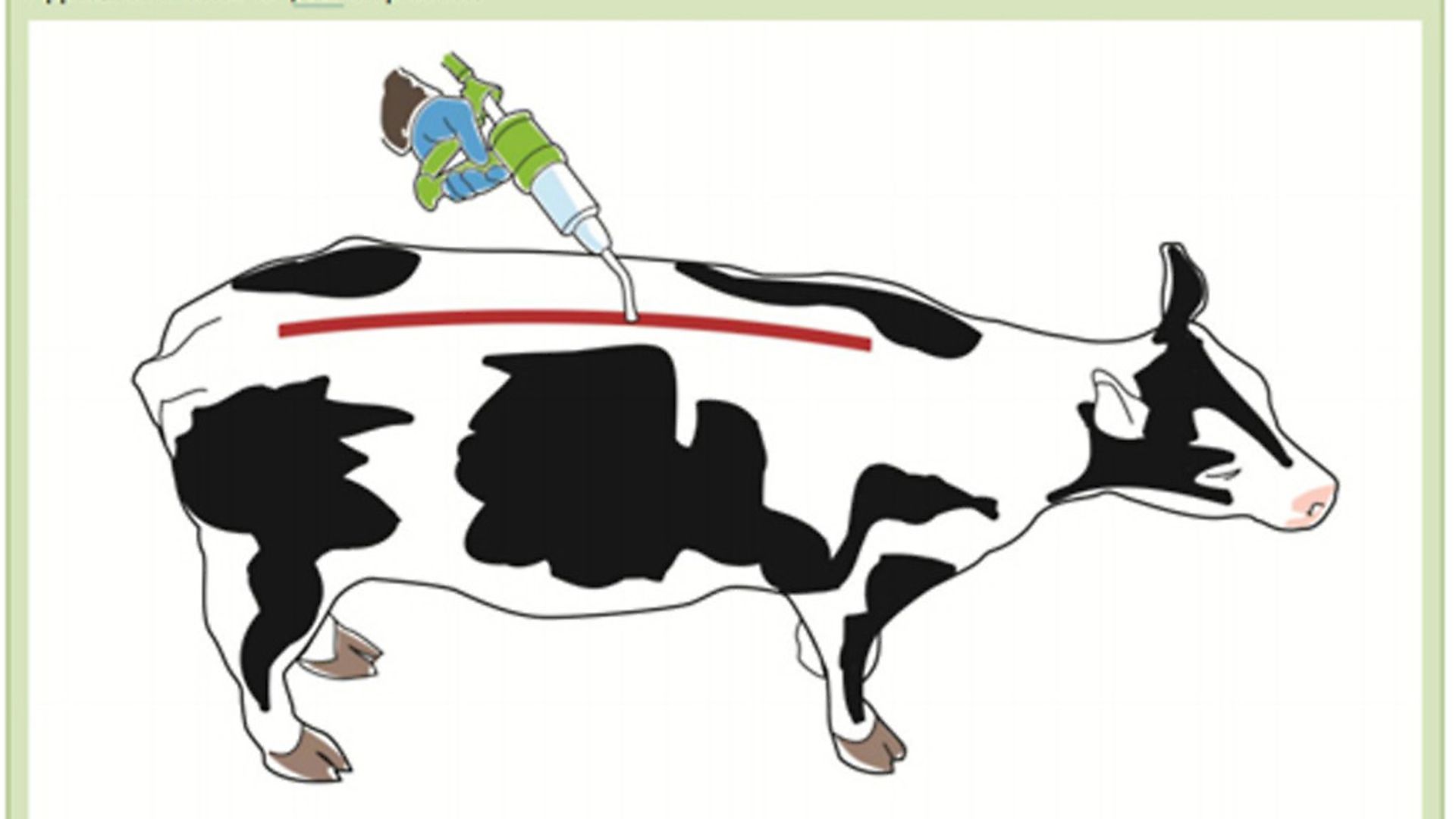

The mainstay of fly control remains the strategic use of pour-on products. Generally these are pyrethroids, similar to the spot-on drugs you would use for parasite control in a dog or cat, although they tend to last longer. A vet will advise on the most suitable product as there are some subtle differences in the length of protection and withdrawal times.

Spot on products require careful application. Apply them along the flattest part of the back from the withers to the tail head, avoiding broken skin or areas covered in mud or manure. In general, they should not be used on wet cattle, or if rain is anticipated. Wearing gloves during application is essential.

Holistic fly control

As with other parasites, there is growing interest in holistic approaches to fly control. This may involve avoiding the worst paddocks during high risk months. It also includes exploring novel repellents.

Mineral lick buckets containing garlic are popular among some farmers as the pungent smell is anecdotally reported to keep flies at bay. There are also several brands of fly-repelling tags which claim to provide a summer’s worth of cover before being removed once temperatures fall again.

On a smallholding you arguably have more control over the fly population of your patch than a farmer does over a large acreage. Fly traps often have impressive hauls and several commercial varieties are available. A cursory search online will also yield hundreds of recipes for home-made traps. Fly strips hung up in buildings seem to kill effectively.

Steps can also be taken to reduce fly breeding habitats. This includes managing dung heaps — try to distance them from livestock. Drain standing water to reduce habitat and likewise site ponds away from grazing areas. Remove dead stock as soon as possible.

Kaz Strycharczyk is a vet with Black Sheep Farm Health, a dedicated farm practice serving farmers located in Northumberland and beyond

Image(s) provided by:

Archant